Aviator Superstitions and Apollo 13

Contributor: Barry Fetzer

Sources: History.com, NASA, American Legion

For those of you reading this who are not aviators, you may not be aware that aviators can be, in general, a suspicious group. Some keep rabbit’s feet (or at least they once kept rabbit’s feet when you could easily get them and having them was more “politically correct”.) I carried one of those mummified “feet” in my flight jacket pocket.

Lucky socks? I knew a fellow squadron mate who had his “lucky socks” that he wore during check rides and other important missions.

Some carry medals of Saint Joseph. According to https://www.picturesongold.com, “Saint Joseph of Cupertino (Italian: San Giuseppe da Copertino), (June 17, 1603-September 18, 1663) is an Italian saint. He was said to have been remarkably unclever, but prone to miraculous levitation and intense ecstatic visions that left him gaping. In turn, he is recognized as the patron saint of air travelers, aviators, astronauts, people with a mental handicap, test takers, and weak students. He was canonized in the year 1767.”

Perhaps the fact that Saint Joseph is the patron saint of people with a mental handicap, test takers, and weak students, it all makes sense that he would also be the patron saint of pilots…and that we carry medals of him for good luck.

Pilots posted photos of their wives and girlfriends on the instrument panel of their aircraft for good luck during WWII…and some even named their aircraft after their wives like “Glamorous Glennis”, Chuck Yeager’s wife and the “Enola Gay”, the Boeing B-29 Superfortress bomber that dropped the atomic bomb on Hiroshima on August 6, 1945, pilot Paul Tibbets’s wife.

Yeager and “Glamorous Glennis”. Courtesy of the American Legion downloaded from https://www.legion.org/information-center/news/landing-zone/2017/october/glamorous-glennis-at-70

I had another personal superstition that involved laying my hand on my aircraft and thanking her following a safe flight and successful mission. And I wore one of those Chinese coins with the hole in the center of it on my flight jacket zipper tab as a “good luck charm”. That coin came from my dad who served in China during WWII and brought it home with him.

So why did NASA decide to keep the number 13, often known as a number of bad luck, on the Apollo 13 mission to the moon? According to AI, “NASA chose to keep the number 13 for the Apollo 13 mission to maintain the sequential numbering of the Apollo program. They believed it was logical and scientific to continue with the sequence, rejecting any notion that a “fateful number” should be skipped. The choice was also influenced by the press, which had been seeking a new angle on the Apollo missions, and superstition around the number 13.”

Did NASA err in not moving beyond the number 13 just as some buildings skip numbering the 13th floor?

Well, NASA’s ill-fated decision to keep Apollo 13 came home to roost on this date in 1970 when, according to History.com and downloaded from https://www.history.com/this-day-in-history/april-11/apollo-13-launched-to-moon “On April 11, 1970, Apollo 13, the third lunar landing mission, successfully launched from Cape Canaveral, Florida, carrying astronauts James A. Lovell, John L. Swigert and Fred W. Haise. The spacecraft’s destination was the Fra Mauro highlands of the moon, where the astronauts were to explore the Imbrium Basin and conduct geological experiments. After an oxygen tank exploded on the evening of April 13, however, the new mission objective became to get the Apollo 13 crew home alive.

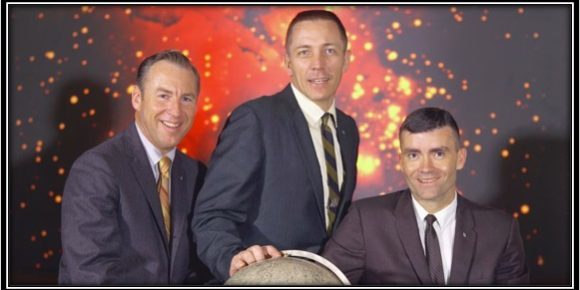

The Apollo 13 astronauts. Courtesy NASA.

“At 9:00 p.m. EST on April 13, Apollo 13 was just over 200,000 miles from Earth. The crew had just completed a television broadcast and was inspecting Aquarius, the Landing Module (LM). The next day, Apollo 13 was to enter the moon’s orbit, and soon after, Lovell and Haise would become the fifth and sixth men to walk on the moon. At 9:08 p.m., these plans were shattered when an explosion rocked the spacecraft. Oxygen tank No. 2 had blown up, disabling the normal supply of oxygen, electricity, light, and water. Lovell reported to mission control: “Houston, we’ve had a problem here,” and the crew scrambled to find out what had happened. Several minutes later, Lovell looked out of the left-hand window and saw that the spacecraft was venting a gas, which turned out to be the Command Module’s (CM) oxygen. The landing mission was aborted.

“As the CM lost pressure, its fuel cells also died, and one hour after the explosion mission control instructed the crew to move to the LM, which had sufficient oxygen, and use it as a lifeboat. The CM was shut down but would have to be brought back on-line for Earth reentry. The LM was designed to ferry astronauts from the orbiting CM to the moon’s surface and back again; its power supply was meant to support two people for 45 hours. If the crew of Apollo 13 were to make it back to Earth alive, the LM would have to support three men for at least 90 hours and successfully navigate more than 200,000 miles of space. The crew and mission control faced a formidable task.

“To complete its long journey, the LM needed energy and cooling water. Both were to be conserved at the cost of the crew, who went on one-fifth water rations and would later endure cabin temperatures that hovered a few degrees above freezing. Removal of carbon dioxide was also a problem, because the square lithium hydroxide canisters from the CM were not compatible with the round openings in the LM environmental system. Mission control built an impromptu adapter out of materials known to be onboard, and the crew successfully copied their model.

“Navigation was also a major problem. The LM lacked a sophisticated navigational system, and the astronauts and mission control had to work out by hand the changes in propulsion and direction needed to take the spacecraft home. On April 14, Apollo 13 swung around the moon. Swigert and Haise took pictures, and Lovell talked with mission control about the most difficult maneuver, a five-minute engine burn that would give the LM enough speed to return home before its energy ran out. Two hours after rounding the far side of the moon, the crew, using the sun as an alignment point, fired the LM’s small descent engine. The procedure was a success; Apollo 13 was on its way home.

“For the next three days, Lovell, Haise and Swigert huddled in the freezing lunar module. Haise developed a case of the flu. Mission control spent this time frantically trying to develop a procedure that would allow the astronauts to restart the CM for reentry. On April 17, a last-minute navigational correction was made, this time using Earth as an alignment guide. Then the re-pressurized CM was successfully powered up after its long, cold sleep. The heavily damaged service module was shed, and one hour before re-entry the LM was disengaged from the CM. Just before 1 p.m., the spacecraft reentered Earth’s atmosphere. Mission control feared that the CM’s heat shields were damaged in the accident, but after four minutes of radio silence Apollo 13‘s parachutes were spotted, and the astronauts splashed down safely into the Pacific Ocean.”

So perhaps Apollo 13 wasn’t so unlucky after all. Certainly, astronauts James A. Lovell, John L. Swigert and Fred W. Haise would agree.

Onward and upward!