This Week in Aviation History: Zeppelins Attack London

Contributor: Barry Fetzer

Sources: History.com, hellfirecorner.co.uk, YouTube

When I was a kid there was a “Boy Scouts-like” and church-based boys’ club called the “Christian Service Brigade” (CSB). We met at our church in Eastlake, Ohio, had uniforms and badges like the Boy Scouts, had camp-outs and attended “Camp Red Eagle” for a week during the summer. But we prayed, read the Bible, memorized Bible verses, and learned about biblical history at our meetings and at camp.

We did fun things like eat cookies and perform science experiments at our meetings. We must have had a science teacher as one of our adult leaders because I remember a couple of the experiments, especially those that resulted in explosions.

What is it about fire, explosions, and boys that fit so well together just like, “…a-wopbop a-doo-wop a-wop bamboo”? I don’t have the answer to that question but I will acknowledge that it’s true, especially for me. I was (and would still describe myself as) a full-fledged “fire bug”.

In one of the two or three CSB meeting experiments I recall from the early 1960’s in the basement of our church, our troop leader created hydrogen gas. He mixed caustic soda (sodium hydroxide) and aluminum foil in water in a flask, and with a series of stoppers and tubes connected to another flask, he inflated a balloon with hydrogen and then in the basement of our church (yes, in the basement of our church…remember, this was the era of playground jungle-gyms on asphalt, metal roller skates with keys but no knee pads, and riding bicycles standing on the seat without helmets) he exploded that balloon in a fiery *pop*, explaining along the way that hydrogen was demonstrateably flammable while the gas, helium, was not.

I remember the troop leader then talking about the USS Shenandoah, the first rigid airship built in the United States, crashing when he was a kid less than 40 years earlier nearby where he lived in Noble County, Ohio, on September 3, 1925. That airship, he explained, was lifted by non-explosive helium as opposed to the highly explosive hydrogen that lifted the WWI German rigid airships or Zeppelins.

You can watch a more modern video of that CSB hydrogen-creating experiment we witnessed at the YouTube video here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ljCJK7eo75g.

Why would I remember all these details from way back when as an eight or nine-year-old boy now 65 years later? It must have been our troop leader-science teacher connecting history with actual explosions and fire. What a great way to teach boys!

Speaking of airship crashes, This week in aviation history allows us to recall Viktor Woellert, the Chief Machinist Mate on the WWI German Zeppelin L31, who was quoted as writing, “I dream constantly of falling Zeppelins. There’s something in me I can’t describe. It’s as if I saw a strange darkness before me, into which I must go.”

Chief Machinist Mate Woellert, as it turned out, was forecasting very accurately his own death. Let’s see how.

According to the History.com editors and downloaded two days ago from https://www.history.com/this-day-in-history/september-8/german-airship-hits-central-london,

German airship hits central London

“On September 8, 1915, a German Zeppelin commanded by Heinrich Mathy, one of the great airship commanders of World War I, hits Aldersgate in central London, killing 22 people and causing £500,000 worth of damage.

“The Zeppelin, a motor-driven rigid airship, was developed by German inventor Ferdinand Graf von Zeppelin in 1900. Although a French inventor had built a power-driven airship several decades before, the von Zeppelin-designed rigid dirigible, with its steel framework, was by far the largest airship ever constructed. However, in the case of the zeppelin, size was exchanged for safety, as the heavy steel-framed airships were vulnerable to explosion because they had to be lifted by highly flammable hydrogen gas instead of non-flammable helium gas.

“The Germans enjoyed great success with the Zeppelin over the course of 1915 and 1916, terrorizing the skies over the British Isles. The first Zeppelin attack on London came on May 31, 1915; it killed 28 people and wounded 60 more. By May 1916, the Germans had killed a total of 550 Britons with aerial bombing.

“One of the best-known Zeppelin pilots was Heinrich Mathy, born in 1883 in Mannheim, Germany. Flying his famed airship L13 on September 8, 1915, Mathy dropped his bombs on the Aldersgate area of central London, causing great damage by fire and killing 22 people.

“The following summer, Mathy piloted a new Zeppelin, the L31 in more attacks on London on the night of August 24-25, 1916. His ship was damaged upon landing; while he was waiting for repairs to be made, Mathy received word that the British had managed for the first time to shoot down a Zeppelin, using incendiary bullets. Shortly after that, Mathy wrote pessimistically: ‘It is only a question of time before we join the rest. Everyone admits that they feel it. Our nerves are ruined by mistreatment. If anyone should say that he was not haunted by visions of burning airships, then he would be a braggart.’ True to his prediction, Mathy’s L31 was shot down during a raid on London on the night of October 1-2, 1916. He is buried in Staffordshire, in a cemetery constructed for the burial of Germans killed on British soil during both World Wars.”

L31 leaves its base at Nordholtz (public domain courtesy of hellfirecorner.co.uk)

Details of the events leading up to L31’s fiery crash follow, downloaded on September 10, 2025 from: http://www.hellfirecorner.co.uk/pottersbar/pottersbar.htm, “At about 11.45 p.m. British aviator Second Lieutenant Wulstan J. Tempest was approximately two hours into his patrol. A large portion of this time had been spent in climbing to bring his BE2c plane to its patrolling height of about 14,500 feet – over two and a half miles high. From this height he saw several of the searchlights to the North of London – about fifteen miles away – converge upon one distant, silvery, cigar-shaped object.

“Tempest, of course, knew exactly what he was looking at, and headed towards the Zeppelin at top speed. He was not the only part of London’s air-defence to have been jolted into action that night – by the time he got closer to the Zeppelin he found himself flying though large amounts of anti-aircraft fire as more and more batteries began firing at the airship.

“Tempest closed with the airship and dived at it, firing a burst from his machine-gun as he approached, and another burst into the underside of the L31 as he passed below. His gun was loaded with a mixture of tracer, incendiary and ordinary ammunition, so he could see that he was hitting his target, but nothing happened. Tempest got unto position under the tail of the ship and fired a long burst as he flew along its length. He saw the envelope begin to glow from the inside like ‘a giant Chinese-lantern’ and then flames began to spurt out of the forward end and almost at once, it seemed, the Zeppelin began to fall.

“The spectacle of the Zeppelin caught so dramatically in the searchlight beams had attracted tens of thousands of people over a wide area. Because of the height involved, the people were able to see it from many miles away. As the tiny jet of flame spread to engulf the ship, an enormous, exultant roar burst forth from the throats of the watchers. At least one photograph was taken. Of course, no-one could see Tempest’s tiny black-painted plane, which was diving as fast as he could make it, trying to get out of the way of the flaming Zeppelin, which roared down directly above him, threatening to engulf him. Tempest managed to spin out of the ship’s line of descent, and flew back to his base.

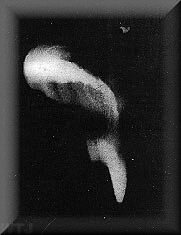

The falling Zeppelin L31 as forecast by Chief Machinist Mate Woellert photographed burning on its way down to its complete destruction (public domain courtesy of hellfirecorner.co.uk).

“It was time for Mathy and for each member of his crew to come to a personal decision. The awful moment they had dreaded had arrived. They must have spent many sleepless hours formulating their answers to the Last Question – ‘Burn or jump – what will you do?’ Now each man had to decide, and quickly.

“Mathy chose to jump. He wrapped a thick scarf (a present from his wife) around his head and leaped from the gondola, falling to earth a little way from the ship, which crashed with an indescribable roar onto the “Zeppelin Oak.” The hissing of burning gas was combined with the wrenching sound of the aluminum framework, the splintering of branches and seconds later, as the burning wreckage settled, the rattling detonations of the Zeppelin’s ammunition and the explosions of its fuel tanks. But Mathy heard none of this. He is sometimes said to have lived for a minute or two after the crash, but this must be no more than myth, Mathy’s reputation investing him with some kind of legendary super-human strength. No-one could have known the truth of this. The fact is for some time, no-one could come anywhere near the wreck, because of the heat and the explosions. There were other dangers, too. A policeman hurrying across the fields was horrified to see one of the L31’s huge propellers cartwheeling madly, coming straight towards him at colossal speed. He dived to one side, watched the propeller demolish a hay-rick and sensibly decided to wait until things had quietened down just a little before going any closer. When Mathy was eventually found, embedded some inches into the soft earth, he was certainly dead. No-one survived the crash.”

The Zeppelin Oak and the remains of the L31 (public domain courtesy of hellfirecorner.co.uk)

Onward and upward!

Sources: History.com, hellfirecorner.co.uk, YouTube