This Day in Aviation History: Laboring in Aviation

Contributor: Barry Fetzer

Sources: Good Fellows Foundation, Creative Commons

My wife, Arlene, and I have been reminiscing about our first jobs today, Labor Day. How about your first jobs?

Mine was washing dishes and pots and pans at a local “greasy spoon” restaurant, named “Paul’s and Hazel’s” when I was 11 or 12. I don’t have a pay receipt from back in 1964 or 1965 to confirm my actual age because I was paid my 50¢ an hour wage in cash directly from the drawer of Paul’s and Hazel’s cash register. Whatever child labor laws may have been on the books back then…well, my parents and “Mister Paul” and “Miss Hazel” looked the other way. In little Mayfield Village, Ohio where we lived, there were no Labor Department officials looking for those employers of kids breaking child labor laws. I’m glad of that. But was I too young?

I don’t think so. I learned a lot from my first jobs, positive traits like grit, timeliness, gratitude, and the value of “showing up” to use and develop whatever God-given talents I have been blessed to receive.

But like many of my fellow Moore County Airport workers and users, I have labored longer in aviation pursuits than any other “job” I’ve held. I put the word “job” in quotes just now because I’ve been blessed to be “laboring” for most of my years of aviation “work” in jobs that I have enjoyed. I haven’t felt like they were real jobs. Unlike many others who may have labored because they had to in order to put on the table, I have looked forward to getting up and going to work most of my life. I have often wondered how I could be paid for the aviation work in which I have been blessed to be involved.

“I love the smell of jet fuel in the morning!” If you’ve never watched the sun rise over a giant aircraft ramp ashore with scores of aircraft parked neatly side-by-side or watched that same sun peek over the horizon of the vast ocean from the deck of an aircraft carrier as you prepare to strap on and launch a powerful machine…well…you’ve missed some life-altering experiences.

I completed private pilot ground school in 1969 as a high school sophomore (while working for a private pilot ground school business as the owner’s “boy Friday”. Enrolled in the US Navy’s “Flight Indoctrination Program”, after getting an aviation flight guarantee while a Navy ROTC student at Ohio State University, I soloed my first aircraft (at the age of 22) in 1975 just before graduating from college. For some 56 years now and still counting, I have “worked” in some way, shape, manner or form in aviation.

Even my current aviation job in aviation ground support at Moore County Airport…I call it my “hobby job” when I describe it to others. I’m grateful that my work—especially that work in and around aviation—has been a personal joy the vast majority of my life. And, more importantly, I hope that most of my laboring has been a joy—or if not a joy, at least a “positive”—to others with whom and for whom I have labored, too.

Fetzer at Moore County Airport with his “Follow Me” cart filled with chocks, July 25. Fetzer Family photo.

But thousands have done far more than me in aviation…my story is nothing compared to so many others in the history of breaking the bonds of gravity. Take, for instance, Bert Acosta, an early American aviator whose aviation exploits are the subject of legend.

According to the Good Fellows Foundation, today (September 1) in 1954, “Bert Acosta passed away. He became the chief flying instructor for the Royal Flying Corps and Canadian Air Service at age 19 where he trained over 400 pilots in Canada without an accident (unheard of at that time). He was responsible for pilot testing, rating other engineers, and approving all planes that saw combat in World War I. He became one of the first civilians to receive an officer’s appointment in the Air Service, with the rank of Captain. He was one of the few civilians to hold both Army and Navy commissions and pilot ratings. In November 1921, in a Curtiss CR-1, Bert became the first civilian to win the Pulitzer Race and Trophy, setting a speed record in the process.

“Three weeks later, in the same airplane, he became the first American to exceed 200 mph. His pilot’s license was suspended for flying beneath the five bridges around New York’s Manhattan Island. In 1928, Connecticut suspended his pilot’s license for trying to fly under the Whittemore Memorial Bridge in Naugatuck. He was later arrested by State Troopers for flying without a license. Nonetheless, in 2014 he was inducted into the National Aviation Hall of Fame.”

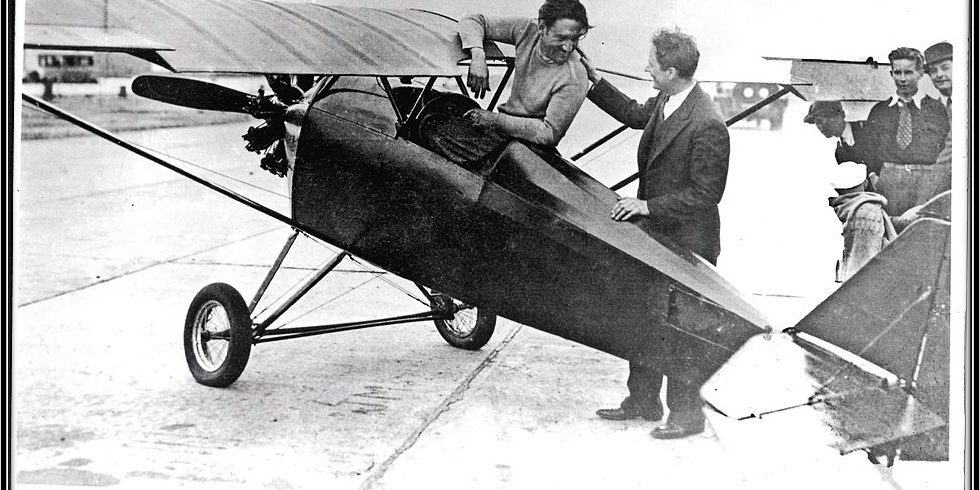

Acosta (left) with Joseph Terleph in c. 1931 following the successful first flight of the Terle Sportplane taken at Roosevelt Field, NY.

This file is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license.

Acosta had a “bad boy” image not unlike some other early aviators who had to have “devil may care” and a “live fast, die young, and have a good-looking corpse” attitude because of the risks and danger of flying in the early days. Ever fly under a bridge? I have not.😊 But I’d guess doing so is some REAL laboring in aviation…a labor of life or death.

Onward and upward!

Sources: Good Fellows Foundation, Creative Commons